We look at the densest objects known to astronomers — black holes — with Dr. Abigail Frost, astrophysicist at KU Leuven

Welcome back to The Cosmic Companion. This week we talk about why Black Holes Don’t Suck as we discuss these bizarre features of space. We’ll talk about the different types of black holes, explore the history of our understanding of these objects, and glance at some of the great questions astronomers have today about black holes.

Later on in the show, we’ll be talking with astronomer and astrophysicist Dr. Abigail Frost about her work finding that the nearest black hole to Earth isn’t a black hole after all!

Black holes are among the strangest objects ever postulated in the annuals of science.

The velocity anything needs to escape from the gravitation well of a planet or star is called (not surprisingly) the escape velocity. If an object shrinks while retaining its mass, the escape velocity goes up. In the most extreme cases, the escape velocity from an object can exceed that of the speed of light. At this point, nothing — not even light — can escape its grasp.

VIP Subscribers view full transcript below

Next week, we look at the future of the International Space Station as we welcome Homer Hickam back to the show! He took part in negotiations with the Russian government as the ISS took shape, and he offers his views of how the war in Ukraine could affect life aboard the orbiting outpost.

Make sure to join us starting 5 April!

VIP Subscribers learn the identity of our special guest for 12 April below!

Thanks for subscribing to The Cosmic Companion!

Clear skies,

James

VIP Transcript (continued)

The earliest ideas of black holes stems back to the 1780’s. As the American Revolution came to a close, an English rector named John Mitchell first envisioned the idea of an object so dense that not even light could escape far from its surface.

The ideas of Mitchell were far ahead of his time, encompassing ideas beyond the world of his time. Naturally, he was rewarded with gifts and fames and accolades… No, I’m kidding. He died in “quiet obscurity” and his ideas were ignored for nearly two centuries.

In 1916, the year after Albert Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity, physicist Karl Schwarzschild developed those ideas into a concise mathematical model of black holes.

Cygnus X-1, a black hole seen in the constellation of Cygnus the Swan, was first spotted in 1964. This discovery provided astronomers their first physical glimpse of a black hole, and also inspired a little over 10 minutes of passable music from Rush.

There are four major types of black holes.

The first of these are stellar-mass black holes. These are the remnants of massive stars which collapse following their deaths.

The second are supermassive black holes. These, as the name suggests, are… supermassive. These behemoths are found near the core of nearly every galaxy. The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, Sagittarius A* (or Sag A star) is four million times more massive than our Sun.

Larger than stellar-mass black holes, yet smaller than supermassive black holes (follow me here, this is where it gets tricky) are intermediate-mass black holes. Their masses — between 100 and 1,000 times that of the Sun — posed a unique challenge for astronomers. They are too large to have formed from stars, and too small to be like those at the cores of galaxies. They MAY be created from the mergers of smaller black holes, or from hungry, hungry black holes gobbling up vast amounts of material from the space in which they reside.

Finally, in 1971, Stephen Hawking introduced the idea of the smallest (and I suspect, the cutest) of these bizarre objects — miniature black holes.

In 2020, astronomers announced the discovery of what they believed to be the closest black hole ever found to Earth, a stellar-mass object a little over 1,000 light years away in the HR 6819 system.

However, a new investigation reveals this system is not likely to be a black hole after all. We talk with Dr. Abigail Frost, astrophysicist at KU Leuven, who helped make this fascinating discovery.

One exciting possibility about black holes is that large numbers of miniature black holes may have formed from gravitational wells during the first second after the Big Bang. The smallest of these could have masses as low as 1/10,000th that of a paperclip.

These may have acted as seeds, growing into the more massive black holes we see today. This idea, proposed five decades ago by Stephen Hawking, has gone in and out of favor over the intervening years.

However, the GAIA mission has found evidence suggesting the presence of large numbers of black holes too small to be the products of the deaths of massive stars.

Gravitational wave detectors have already seen mergers of black holes, and could prove to be means for astronomers to find evidence of primordial black holes from evidence of their mergers.

If primordial black holes exist, which is far from certain, they could help explain the mysterious dark matter which appears throughout the Cosmos. The largest of the primordial black holes could have been born in powerful gravitational wells, tens of thousands of times more massive than the Sun.

This intriguing possibility leaves astronomers with a massive problem about black holes — did they form in the primordial Cosmos, or did the first black holes form from the collapse of massive stars hundreds of thousands of years after the Big Bang?

If primordial black holes formed in the first instant of the Big Bang, their presence in the early Cosmos would have drawn matter together, forming stars sooner after the Big Bang, than would otherwise be expected.

The James Webb Space Telescope is designed to see the earliest light in the Universe. Using this instrument, astronomers should learn when the first stars in the Cosmos came ablaze with light.

This finding could “shed light” on the darkest objects in the Universe.

VIP Subscriber Insider Info!

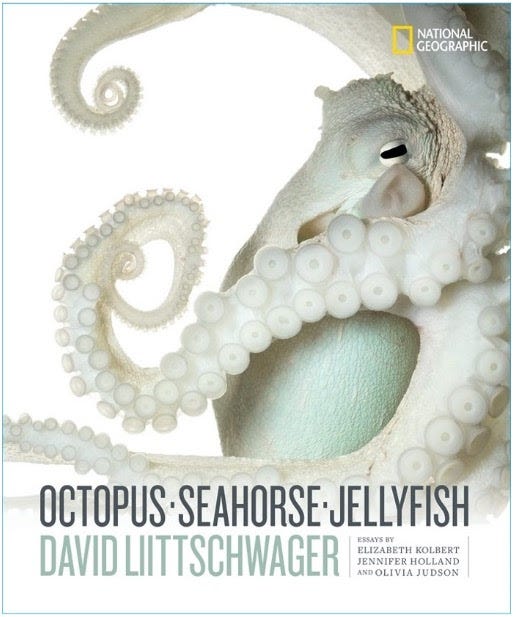

On 12 April, we will look at Intelligence: Earth and Beyond with David Liittschwager, author and photographer of Octopus Seahorse Jellyfish, coming soon from National Geographic.

We will talk about the nature of intelligence, how we recognize intelligence in organisms far different from us, and how we might recognize intelligent life when we find it on other worlds.

Make sure to join us then!

Thanks SO MUCH for being a VIP subscriber!

James

Share this post